In 2023, I published the book Cultural Violence, Stigma and the Legacy of the Anti-Sealing Movement (Routledge). The book focused on the rural and coastal Newfoundland and Labrador experience with anti-sealing activists and activism. It also includes reflections on Indigenous experiences with anti-sealing activism. I made the case that anti-sealing activists pursued an agenda of cultural violence to achieve their aims, as evidenced by the attitudes, actions and behaviours of activists. It also highlighted the central role of activist supports including politicians and governments such as the European Economic Community/European Union and the impacts of activism on rural and coastal Indigenous and non-Indigenous sealers/fishers, their families, communities and societies at large.

The subject of cultural violence was pioneered by Johan Galtung (1990, p. 291) who describes cultural violence as the “aspects of culture, the symbolic sphere of our existence – exemplified by religion and ideology, language and art, empirical science and formal science (logic, mathematics) – that can be used to justify or legitimize direct or structural violence.” The research on cultural violence is imbedded in the literature on cultural genocide.

Cultural genocide was coined by Robert Lemkin and his struggle to get recognized for the scale of destruction beyond just physical genocide during the development of human rights law in the post-Second World period (Novic 2016; Payam 2016; Berster 2015; Kingston 2015). In Canada, cultural genocide has gained a lot of contemporary attention given its recognition as part of the decolonization process and the reconciliation with the state’s Indigenous nations, in particularly the legacy of the Indian Residential School system and its destructiveness on cultural connections and generational knowledge transfer within the societies of Indigenous nations across Canada.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission defines cultural genocide as “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group” (Truth and Reconciliation Report 2015). The growing recognition of instances of cultural genocide enables greater reflection on the value and inclusion of intangible elements of culture such as languages and traditional practices in societies (Belsky and Klagsbrun 2018; Mullen 2020).

As I review holdings collected at the Laurier Archives and Collections based at the Wilfrid Laurier University and reflect on what I, and my culture, have experienced as a rural Newfoundlander and what I have learned over the years researching this subject about the impacts of anti-sealing activism on rural and coastal fishing communities across the Circumpolar North, I have begun to wonder, was I wrong? Have I underestimated the scale of the violence when I attempted to navigate the unclear boundary between when instances of cultural violence occur and when they escalate to cultural genocide in my research?

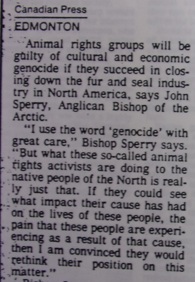

What is clear to me so far based off of my review of materials from the Laurier Archives and Collections is that concerns that anti-sealing activism bordered on cultural (and economic) genocide is not an original thought of mine. This concern was being articulated in the 1980s, at the height of anti-sealing activism.

In 1986 John Sperry, Anglican Bishop of the Arctic, a man who moved to the Canadian Arctic in 1950, stayed, and integrated including learning Innuinaqtun (Csillag, 2012), flagged the potential for anti-sealing activism to escalate into genocide; “Animal rights groups will be guilty of cultural and economic genocide if they succeed in closing down the fur and seal industry in North America” (Canadian Press, 1986). The Canadian Press reports that Sperry went on to state:

“I use the word ‘genocide’ with great care…But what these so-called animal rights activists are doing to the native people of the North is really just that” (Canadian Press, 1986). And it is not just native people who were severely impacted, as my 2023 book outlines with a focus on the Newfoundland and Labrador experience, for example (Burke, 2023).

The Indigenous advocacy organisation Indigenous Survival International similarly stressed in 1985 the depth of the destruction being pushed by animal rights activists in the name of progress: “The animal rights movement…is a blatant violation of our human rights. It is no different from the multi-national corporations who invade our homelands to exploit our resources, pollute our rivers, and poison the fish and wildlife which are our sources of food…If an intent to destroy our Peoples, in whole or in part, could be established on the part of the animal rights activists, then, their actions would be tantamount to genocide” (Indigenous Survival International, 1985, p. 4).

At the time that the above statements were made the percentage of sealers, in Canada at least, was reportedly evenly split between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures.

In Canada, 50% of trappers are estimated to be native. Surveys by both governments and aboriginal organizations confirm the 50% figure. And numbers can in no way convey how important trapping is in Canada’s North, where most of the aboriginal inhabitants derive some benefit, directly or indirectly, from the activity (Woods, 1986).

Therefore, though the concern of cultural and economic genocide in the Sperry and Indigenous Survival International statements above stress concerns for Indigenous peoples, the threat of genocide was not solely to Indigenous cultures.

Sadly, as my book highlights, anti-sealing violence did not stop in 1985-86. The erosion and active stigmatization of Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural and economic traditions and practices connected to sealing has grown progressively worse. Reflecting on this period brings warnings, such as Bishop Sperry’s, to mind. If he could observe on the ground in the 1980s that cultural and economic genocide was on the horizon as a result of the animal rights agenda toward sealing, and other fur trading, then at what point does a looming threat of genocide transition into the reality of genocide?

Part of my contemplation of cultural violence and cultural genocide stems from knowledge of an interesting IFAW statistic, and the organisation’s accompanying core belief. IFAW is a central and leading organisation throughout the decades of anti-sealing activism. The organisation credits itself, with European politicians it lobbied, for bringing about a 90 percent decrease in the number of sealers in Canada by the 1990s through the establishment of bans on seal product imports in the European market (IFAW n.d.). This 90 percent decrease is highlighted by the organisation as a crowning achievement; reflecting that for IFAW a core belief is that its anti-sealing agenda and the outcomes it has help bring about are points of pride.

My book Cultural Violence, Stigma and the Legacy of the Anti-Sealing Movement unpacks aspects of the peoples, experiences and implications behind that number: 90 percent. But perhaps calling the anti-sealing experience of rural and coastal peoples and their communities cultural violence does these people and cultures a disservice.

IFAW actively celebrates and promotes its legacy of fostering the global devaluation and near eradication of centuries old cultural and economic sealing traditions. It ignores the fact that with the loss of 90 percent of Indigenous and non-Indigenous practitioners, especially in rural and isolated locations and in such a short period of time, there is a significant loss of generations of traditional marine ecological and community knowledge held by Indigenous and non-Indigenous sealers. Similarly, the loss of 90 percent of sealers also means the loss of status and roles for people within their cultures, triggering the breakdown of the social fabric of their societies in the Circumpolar North.

It’s that number – 90 percent – that is so jarring. If the statistic is correct, I struggle to make a case that the active pursuit of the eradication of sealers does not reach the threshold of cultural and economic genocide. IFAW, and its allies especially in Europe, pursued this agenda. And they appear to be proud of it.

It’s a lot to digest. And I think the answer to my core question – was I wrong? – is yes, at least in part. Is the legacy of anti-sealing campaigning one of cultural violence as I previously argued. Yes. But are we at a point where the situation has progressed and now cultural and economic genocide against rural and coastal Indigenous and non-Indigenous sealing cultures in the Circumpolar North and bordering areas has been, and continues to be, committed? Evidence is increasingly indicating that it is.

References:

Belsky, Leora and Klagsbrun, Rachel. (2018).”The Return of Cultural Genocide?” The European Journal of International Law 29: 373-396.

Berster, Lars. (2015). “The alleged non-existence of cultural genocide.” Journal of International Criminal Justice 13: 677-692.

Burke, Danita Catherine. (2023). Cultural Violence, Stigma and the Legacy of the Anti-Sealing Movement. Routledge.

Canadian Press. (1986). “Animal rights activists hurt Inuit, bishop says”. Laurier Archives, Canadian Arctic Resources Committee fonds S469, Box 270, File 13.1.21(1).

Csillag, Ron. (2012). “John Sperry, Pioneer Bishop”. March 12, 2012. The Living Church. Available at: https://livingchurch.org/news/john-sperry-pioneer-bishop/# (Accessed April 4, 2025).

Galtung, Johan. (1990). “Cultural Violence.” Journal of Peace Research 27: 291-305.

IFAW. (n.d.) “IFAW was first founded to end the seal hunt.” https://www.ifaw.org/ca-en/projects/ending-the-commercial-seal-hunt-canada.

Indigenous Survival International (1985a) “Indigenous Survival International (ISI): Submission to the Canadian Royal Commission on Seals and the Sealing Industry”. London, England. April 9, 1985. Laurier Archives, Canadian Arctic Resources Committee fonds S469, Box 48(1), File 2.9.3.

Kingston, Lindsey. (2015). “The Destruction of Identity: Cultural Genocide and Indigenous Peoples.” Journal of Human Rights 14: 63-83.

Mullen, Ashley. (2020). “International Cultural Heritage Law: The Link Between Cultural Nationalism, Internationalism, and the Concept of Cultural Genocide.” Cornell Law Review 105: 1489-1526.

Novic, Elisa. (2016). The Concept of Cultural Genocide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Payam, Akhavan. (2016). “Cultural Genocide: Legal Label or Mourning Metaphor?” McGill Law Journal 62: 243-272.

Woods, Shelagh Jane. (1986). Letter to George Clements, Executive Director, Executive Director, Association of the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals from Shelagh Jane Woods, Policy Advisor, Canadian Arctic Resources Committee. August 5, 1986. Laurier Archives, Canadian Arctic Resources Committee fonds S469, Box 270, File 13.1.21(1).

Author: Danita Catherine Burke (Copyright of Laurier Archives photograph – D. Burke)